I work at UC Davis, a University with at least two (that I know about) centers devoted to research “aimed at developing a sustainable market for plug-in vehicles.” I run into a lot of researchers and environmental advocates who are completely dedicated to the mission of accelerating the deployment of electric vehicles. They view electrifying a large share of the transportation fleet as one key piece of the climate policy puzzle.

I am also an economist. The research coming out of the economics community has pretty consistently demonstrated that electric vehicles currently have marginal (at best) environmental benefits. I run into a lot of economists who are perplexed at the hostility these findings have generated from pockets of the environmental community.

I have followed and pondered these clashes for some time now, in part for the entertainment value, but also because of what this conflict reveals about how the different disciplines think about climate policy.

As the Paris climate summit concludes, the spotlight has been on goals such as limiting warming to 2 or even 1.5 degrees Celsius, and how the agreed-to actions fall short of the necessary steps to achieve them. There has been much less focus on where targets like 2 degrees Celsius come from, and what the costs of achieving them would be. A lot of the policies being discussed for meeting goals like an 80% reduction in carbon emissions carry price tags well in excess of the EPA’s official “social cost of carbon,” one measure of the environmental damages caused by CO2 emissions. It is quite likely that these different perspectives, about how to frame the climate change problem, will define the sides of the next generation of climate policy debate (if and when we get past the current opposition based upon a rejection of climate science).

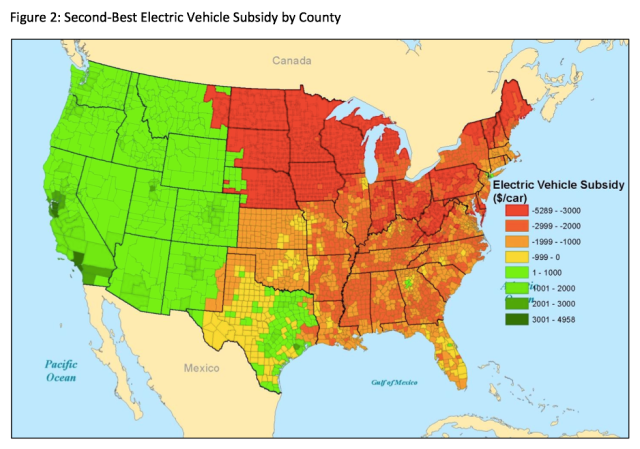

To be clear, the research on EVs is not (for most places) claiming that electric cars yield no environmental benefit. The point of papers like Mansur, et. al, and Archsmith, Kendall, and Rapson is that these benefits are for the moment dwarfed by the size of public and private funds directed at EVs. Some have criticized aspects of the study methodologies (for example a lack of full life cycle analysis), but later work has largely addressed those complaints and not changed the conclusion that the benefits of EVs are substantially below the level of public subsidy they currently enjoy. Not only that, but Severin Borenstein and Lucas Davis point out that EV tax credits are about the most regressive of green energy subsidies currently available.

Another common, and more thought provoking, reaction I’ve seen is the view that the current environmental benefits of EVs are almost irrelevant. The grid will have to be substantially less carbon intensive in the future, and therefore it will be. The question is, what if it’s not? It seems likely that California will have a very low carbon power sector in 15 years, but I’m not so sure about the trajectory elsewhere. This argument also raises the question of sequencing. Why are we putting so much public money into EVs before the grid is cleaned up and not after?

This kind of argument comes up a lot when discussing some of the more controversial (i.e., expensive) policies directed at CO2 emissions mitigation. Economists will write papers pointing to programs with an implied cost per ton of CO2 reductions in the range of hundreds of dollars per ton. One reaction to such findings is to point out that we need to do this expensive stuff and the cheap stuff or else we just aren’t going to have enough emissions reductions. Since we need to do all of it, it’s no great tragedy to do the expensive stuff now.

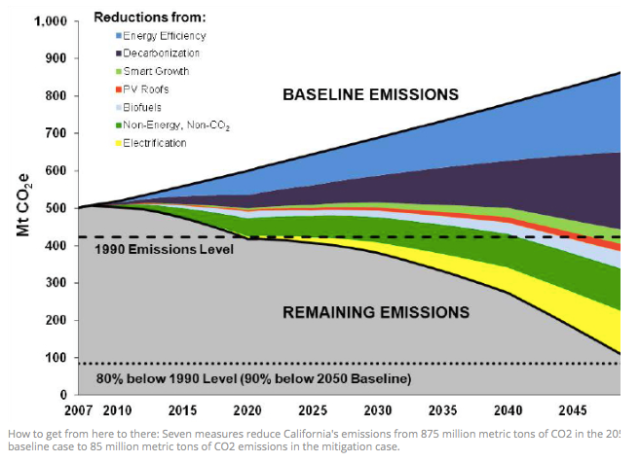

It seems to me that this view represents what was once captured in the “wedges” concept and is now articulated as a carbon budget. Environmental economists call it a quantity mechanism or target. The underlying implication is that we have to do all the policies necessary to reach the mitigation target, or we are completely screwed. So we need to identify the ways (wedges) that reduce emissions and get them done, no matter what the costs may be.

According to this viewpoint we shouldn’t quibble over whether program X costs $100 or $200 a ton if we’re going to have to do it all to get the abatement numbers to add up. Sure, it may be ideal to do the cheap stuff (clean up the power sector) first and then do the expensive stuff (roll out EVs), but we’re going to have to do it all anyway.

At the risk of oversimplification, many environmental economists think of the problem in a different way. Each policy that reduces emissions has a cost, and those reductions create an incremental benefit. The question is then “are the benefits greater than the costs”? From this framing of the problem, a statement like “we have to stick to the carbon budget X, no matter what the costs” doesn’t make sense. Any statement that ignores the costs doesn’t make sense.

It does appear that to reduce emissions by 80% by 2050, we will have to almost completely decarbonize the power sector and largely, if not completely, take the carbon out of transportation. That’s just arithmetic. How does one square that with research that implies such policies currently cost several hundred dollars a ton?

In particular, how do we reconcile this with the EPA’s estimates of the social cost of carbon that are in the range of $40/ton? In their paper on the lifecycle carbon impacts of EVs and conventional cars, Archsmith, Kendell, and Rapson, using $38/ton as a cost of carbon, estimate the lifetime damages of the gasoline powered, but pretty efficient, Nissan Versa to be $3200. In other words, replacing a fuel efficient passenger car with a vehicle with NO lifecycle emissions would produce benefits of $3200. That puts $10,000 in EV tax credits in perspective.

Many proponents of those policies no doubt believe that the benefits of abatement (or costs of carbon emissions) are indeed many hundreds of dollars per ton. Or they could believe that costs of many of these programs are either cheaper right now than economists claim, or will become cheaper over the next decades. Some justify the current resources directed at EVs as first steps necessary to gain the advantages of learning-by-doing and network effects. Others make the point that the average social cost of carbon masks the great disparity in the distributional impacts of those costs. Perhaps climate policy should be trying to limit the maximum damages felt by anyone, instead of targeting averages. How do residents of the Marshall Islands feel about the US EPA’s social cost of carbon?

All these are legitimate viewpoints. However, there is also the fact that the quantity targets we are picking, like limiting warming to 2 degree Celsius increase and/or reducing emissions by 80% by 2050, are somewhat arbitrary targets themselves. It’s hard to claim that the benefits of abatement are minuscule if we fall slightly short of that target and suddenly become huge if we make it. This encapsulates the economists’ framing of the climate problem as a “cost-based” one. Under this viewpoint we should keep pushing on abatement as much as we can, and see if the costs turn out to be less than the benefits. If not, we adjust our targets in response to what we learn about abatement costs (in addition to climate impacts).

This motivates so much of the economics research focus on the costs and effectiveness of existing and proposed regulations. That community doesn’t view it as sweating the small stuff. Under this framing of the issue, maybe having a fleet of super fuel efficient hybrids makes more sense, even if it results in higher carbon from passenger vehicles than a fleet of pure EVs might.

Or maybe EVs do turn out to be the best option. The two sides will have to recognize where the other is coming from, or the next round of climate policy debates may be as frustrating as this one.

Davy on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 11:18 am

“You wouldn’t be posting in this thread if the government hadn’t become actively involved in technological development (Arpanet).”

Enu, we can debate the good and bad but I have seen many examples of government involvement that has been destructive. Many times government has been bought off for private gain at the public expense.

Electric cars have a niche but I don’t see anything transitional. We are out of time, resources, and the social fabric is uninterested to make revolutionary changes. Electric transport is a domaine of the rich and the highly motivated greens. Normal people have little interest and their lives are not flexible enough to to go electric.

The economics and the effectiveness of the technology is not impressive. Currently ev is fossil fuel driven mostly. It is another bullet but no silver bullet the techno-greens believe it too be.

Phil Wood on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 11:24 am

There is a finate amount of Carbon on this planet. Tere will never be any more or any less. CO2 is “scrubbed” by plants in the process of making Oxygen (this cannot change). Electric vehicles (as we currently have them) are basically just toys with very modest use to anyone. It sounds good to use public transit but, most areas do not have it. Even in many major cities (Dallas is a good example) you have limited or no transportation except for M-F daytime only if they have public transit at all. The only transit that exists in most places is private vehicles. I like having my yard (it is small only 150×150′) and having my RV (kept at my house of course). Give ma a viable alternative and I wil consider it-so far there is nothing in sight. I have a degree in biology/chemistry and have worked in environmental for over 40 years, I have read more than one book, and have never hugged a tree. That in itself makes it imposible for me to be an environmentalist.

peakyeast on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 12:23 pm

@pete: Please show me the calculation..

And please include the expected lifetime of the vehicle including battery.

Since the battery of a tesla is 30000$ and you must expect two replacement that should be included for the lifetime of the car.

My ICE cars would be due for their 3rd battery change, but are doing very well without what is basically the value of a brand new mini car today.

Pete Bauer on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 1:11 pm

Batteries in many Hybrids have already done 500,000 miles (800,000 km). Here is 1 Prius which has done 1 million km which is more than 600,000 miles.

http://www.carscoops.com/2013/12/toyota-prius-hybrid-taxi-clocks-1.html

Motors are lot more durable and needs lot less maintenance and this is already shown in many electric trains.

As for the calculation check the mileage of EVs / Plugins in any website and they will show the mileage as 100 MPGe, 110 MPGe and so on.

As for the Tesla’s battery, you don’t need to replace the battery in 10-15 years. So don’t worry about the battery.

GregT on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 1:33 pm

“You wouldn’t be posting in this thread if the government hadn’t become actively involved in technological development”

I’m sure that life will continue on without the internet.

GregT on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 2:13 pm

“Greg, do I get under your skin?”

No Davy, I feel sorry for you. America is/was a great country, that still has millions of exceptional individuals. People like you are making decent Americans everywhere look bad. You are an ugly American Davy. I’m done pandering to you.

Davy on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 4:06 pm

To those folks who think building out a brand new EV network is in order I would remind you of all those fossil fuel vehicles that are paid for so to speak. The planet, through humans has built out a huge infrastructure. The damage has already been done. It is paid for. I don’t see how retiring this infrastructure and building a new one can pencil out on multiple levels.

The biggest issues by far is the grid is fossil fueled powered for the most part. If we had an abundance of alt power to spare I could understand the need for ev. I am all for ev niche applications where companies and individuals can utilize alt energy to power ev’s. My point is it will never scale in the bigger picture. It would be far better to focus on localization as an alternative. Localization will not be cheap but it pays off by far over any technical option.

peakyeast on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 6:39 pm

@pete: Hybrids are not electrical cars. They are an expensive over complicated tradeoff.

Tesla themselves from what i have seen says that if the battery falls below 70% charge before 8 years it is a warranty replacement. The reason why they dont say 70% after 10 years is probably because they know that will give them too many replacements.

So can you accept an e-car where most of them has JUST enough at 100% to function in a normal persons life being reduced to for example 50%?

Now dont come up with they can drive this long at 100% – because no-one wants to use 100% of their battery every day. And when it is cold and you need a little heating the distance is reduced significantly from what the owner I have talked with.

So no.. You have to replace the battery when – also in teslas.

If not please document why.

peakyeast on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 6:41 pm

Tesla is not the norm – they have more km/charge than most – and we are talking about electric cars for the people – not just the 1% rich people.

BobInget on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 7:04 pm

I won’t bore everyone with my TDI saga with VW. Except to say, we ain’t finished yet.

Just bought a new e.Golf with money from VW’s guilt trip rebate.

Since we’ve had a major solar array for years,

I don’t ever expect to pay for auto fuel around hometown again. Oh, love the car.

It’s quicker off the mark then either of my diesels, Golf or Jetta and so, so, quiet.

A trickle charger, level three, charges batteries, from 90% empty to full in about 20 hours. I decided to spring $400 for a level two charger, that does the job in two hours, just in case.. ( my 68 year old bride needs to

hit the maternity ward just as I came home from golfing)

Siemens offers to rebate the entire cost of the charger if a person puts up solar panels.

Oh, my combined tax rebates from Fed and State comes to $7,500. Plus, obviously, no gasoline taxes, for now at least. My state is changing over to miles driven taxes.

Standard joke at the dealership is an offer of free oil changes for life when buying any electric car. They charge $500 for ICE engine

lifetime oil changes.

The VW e.Golf comes with electric heat, seats and cabin, that goes on instantly, no waiting for engine warm-up.

(both heat and AC are brought to us by ‘heat pump,’ saving battery power.

The car comes with a deep cycle 12 Volt battery, powering windows, wipers, radio etc.

The 12 V also acts as reserve power that kicks in if a person ‘runs outta gas’.There’s ample room for another 12 V battery if you are the belt and suspenders type. I bet after market sellers will come up with compact Lithia 12V.

Anonymous on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 7:22 pm

Comparing the supposed durability of hybrid batteries to a full-blown EV is what one would call, irrevelent. ‘Hybrids’ are not EV’s. Their batteries do very little actual propulsion, the gas motor does nearly 100% of the heavy lifting. The battery, only kicks in infrequently at best and only for very limited times and ranges. And yes, electric motors are in fact quite durable and long lived, and require far less maintenance than oil burners. But ‘hybrids’ don’t operate on those either.

peakyeast characterization of them is right on. ‘Hybrids’ are not EV’s. They are a blend of soso oil burner and totally ineffective ‘EV’. ‘We’ could easily build all oil powered cars with better mileage and no less polluting, but ‘hybrids’ are such great marketing tools they aren’t about to go that route. You can keep wrecking the planet with your ‘hybrid’ and not feel guilty about it too. Priceless.

makati1 on Sat, 19th Dec 2015 9:14 pm

One question, where do the rare earths come from for these batteries?

I understand that the Us imports almost all of it’s rare earth needs. Interesting fact in a world where globalization is also in contraction. Maybe those battery replacements will not be available when needed?

Not that electric cars or hybrids will ever be more than a toy for the techie upper class or their wannabees. Three million is less than 0.3% of the total cars in the world today. There are more golf carts by far. LOL

GregT on Sun, 20th Dec 2015 1:13 am

“Just bought a new e.Golf with money from VW’s guilt trip rebate.”

Good for you Bob. A smart decision, a great choice for the ‘transition’, and will in all likelihood serve you well for the remainder of your life.

EV’s are not in humanity’s near term future, however.

Davy on Sun, 20th Dec 2015 8:07 am

How does $1000 VW guilt rebate make a difference in buying a new car? That’s what my rebate was. I love my TDI Jetta. I get 45MPG highway. I have not done the research but you would think that kind of efficiency would translate into lower emissions compared to a vehicle with half that MPG. City MPG is not great but I use my Jetta for highway driving.

rdberg1957 on Sun, 20th Dec 2015 10:35 am

Individual EV’s are unlikely to be an environmental benefit given what goes into producing them. Electric transportation could be a huge benefit, but it would not involve individual ownership of vehicles.

Davy on Sun, 20th Dec 2015 12:39 pm

EV transport is best for mass transit or small transit. I see cities with mass transit powered by alts as a proper use. This could be micro mass transit for small communities. I love incongruous juxtapositions. Personal ev lacks practical scaling except for golf cart size applications. Keep it simple at the mini end and make it mass transit for the more complex.

Revi on Sun, 20th Dec 2015 4:44 pm

How can cars that weigh 3000 pounds and can only get 4 people around possibly work into the future? I know that they get 50 mpge, but the fact is that is still a lot more fossil fuel use than if those 4 people went by train, then walked around in an urban setting. Small EV’s could work, but just for local transportation.

makati1 on Sun, 20th Dec 2015 8:08 pm

Here in the Ps, trikes (small motorcycles with a modified sidecar) can and do move anywhere from 1 to 5 passengers around the city. It is not unusual to see 2-3 passengers plus their baggage on board, going down the street. It would be illegal in the Us where helmets and seat belts are required by all, and the insurance companies would price it out of existence. Yet, it moves millions everyday, safely and with minimal energy use or cost.