Page added on January 23, 2018

Why the oil price is so high

PERHAPS the most vexing thing for those watching the oil industry is not the whipsawing price of a barrel. It is the constant updating of theories to explain what lies behind it. In March 2014, when the price of a barrel of Brent crude was in three figures, the then boss of Chevron, an oil giant, observed that the scarcity of cheap oil meant “$100 per barrel is becoming the new $20”. Two years later, when the oil price slumped below $28, the talk was of a global oil glut caused by the furious efforts of the OPEC cartel to regain market share. Now that oil prices have tested $70, analysts are again scratching their heads.

In “1984”, George Orwell coined the term “doublethink”, the ability to believe two contradictory things. Oil analysis seems to require similar cognitive gymnastics. Three big questions arise. First, why has the oil price more than doubled in the space of two years, against all expectation? Second, why has this surge been met with cheers from global stockmarkets and not concern for the world economy? Lastly, where might the oil price eventually settle?

Start with the journey to $70. The slump in prices two years ago was in part a response to weak demand—with the fragility of China’s economy a big concern—and in part to abundant supply. Few believed then that OPEC would, or even could, cut output. Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, appeared to have every reason not to. Plentiful oil supply would check the growth of the shale-oil industry in North America. It would also stymie Iran, its bitter rival, which was back in the market following the lifting of sanctions.

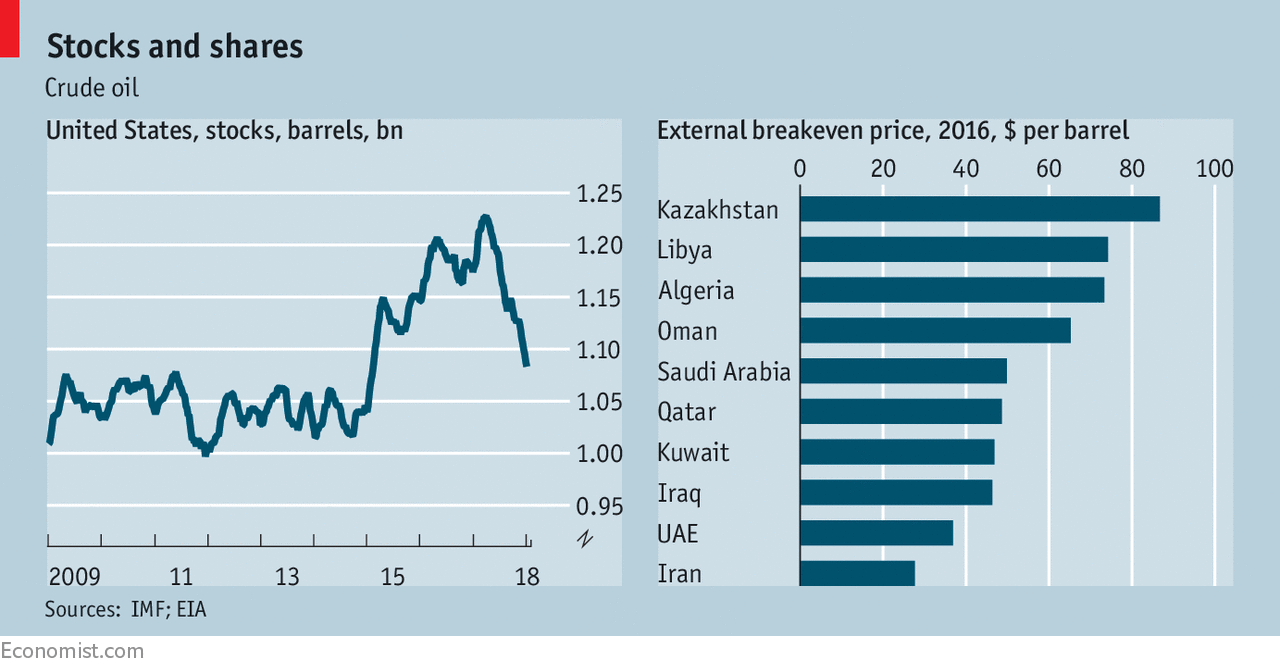

Yet demand recovered quickly. China pepped up its economy with faster credit growth and other fillips to spending. Commodity prices surged. Within months clear signs of a broad-based global economic upswing were palpable. And OPEC proved better able to curb production than anyone had imagined. A deal reached in November 2016 to restrict output had little immediate effect but by late last year started to pay off. Oil stocks fell, notably in America (see left-hand chart). Demand was outstripping supply. Prices duly rose.

It is still surprising they have risen so far. Higher prices are often blamed in part on the messy politics of the Middle East. The usual worries are there but “there has been no impact on physical supply,” says Martijn Rats of Morgan Stanley. Shale was also seen as the oil industry’s flexible response to price signals. Too high, and the wildcatters in Texas would drill for fresh supply. But small producers are showing a new restraint, because their financiers want greater focus on profits and less on output. And it takes several months from drilling wells for oil to come on-stream.

The financial markets show little sign of anxiety about the oil-price surge. Stockmarkets remain buoyant, which is itself another puzzle. Since the oil shocks of the 1970s, markets have associated a sudden run-up in oil prices with economic calamity. The world is both producer and consumer of oil, so in principle the overall effect of oil-price increases is neutral. But in practice, the net impact had been to reduce global demand, because oil exporters in the Middle East tended to save a big chunk of the windfall income they gained at the expense of oil consumers in the West.

Over time, however, the rich world has become less reliant on oil. Demand in America peaked in 2005, for instance. Meanwhile, oil exporters became ever more dependent on high oil prices to pay for lavish government budgets and imported consumer goods. Most of the big oil producers in the Middle East need an oil price above $40 to cover their import bill (see right-hand chart on previous page).

In this new arrangement, dearer oil is both far less damaging to rich-world consumers and soothes the strained finances of the big oil exporters, not just in the Middle East but in Africa, too. For all the other trouble-spots, investors seem to find the world economy a safer place. And they have other reasons to feel cheery. The shale industry means that dearer oil is a shot in the arm for investment in America, which adds to GDP growth. And a rising oil price is taken as a sign of healthy growth in China, the world’s biggest oil importer.

Beneath the dramatic ups and downs in the oil price and its changing influence on the world economy are some big themes: the rise of the shale-oil industry and how OPEC responds; the dependence of the big oil exporters in the Middle East on high oil prices; the peak in oil demand in America and eventually elsewhere. These forces will have a big say in where oil prices eventually settle.

How they will play out is the subject of a new paper by Spencer Dale, chief economist of BP, another oil giant. The critical change in the oil market, he argues, is from perceived scarcity to abundance. When oil was considered scarce and expensive to find, it seemed wise to ration it. It was more like an asset than a consumer good: oil in the ground was like money in the bank. But new sources of supply, such as shale oil, and improved recovery rates of existing reserves, along with the emergence of mass-market electric vehicles, have changed the reckoning. There is a fair chance that much of the world’s recoverable oil will never be extracted, because it will not be needed. It thus makes sense for the five big producers in the Middle East (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, Iraq and Kuwait), which can extract oil for less than $10 a barrel, to undercut high-cost producers and capture market share while the demand is there. The financial logic has changed to “better to have money in the bank than oil in the ground,” notes Mr Dale.

Does that mean oil prices are poised to plummet? Probably not, unless shale producers ramp up output again. The peak in global oil demand might be decades away, argues Mr Dale, and it will not tail off sharply. And for now, the big oil exporters cannot sustain very low oil prices for long. Their “social cost” of production, taking in government spending reliant on oil revenue, is about $60 a barrel on average. Sustaining an oil price close to the cost of extraction will require reforms, which do not usually happen quickly. Translated into doublespeak: oil prices are too high; but they may not fall, in large part because big oil producers have got used to them.

8 Comments on "Why the oil price is so high"

Sissyfuss on Tue, 23rd Jan 2018 8:43 pm

Another example of Orwells doublespeak is that we can grow the economy and the population, and the environment will be just fine.

Boat on Tue, 23rd Jan 2018 9:13 pm

1 st it was fracking and oil sands that causedvthe glut if you were counting the barrels.

2 nd demand was strong not weak as stated.

3 rd scratching head did not happen as oil went to $70. OPEC/Russia cut production.

The cartel gave up market share to get their $70. They can control the price by their actions. You can have volume or price. Frackers make sure of that by drilling at 40 and up. Drilling more at $50, at $60 like now? Over 100,000 bpd growth per month.

rockman on Wed, 24th Jan 2018 11:01 am

And once again the simplistic effort to explain a complex dynamic with a bumper sticker: A happened which completely explains why B happened.

Oil producers do not set the price they sell their oil for. But they can adjust the volume they produce which MIGHT have some effect. But not a guarantee. Even if they reduce production the refineries will not pay more for a bbl of oil that they estimate will produce a loss. And how do the refineries make that estimate? By projecting what they anticipate consumers will pay for their products. Even if OPEC cut production by 10 mm bopd the refineries might pay even a lower price then they are today. And would do so if they projected a decrease in consumer demand at that oil price.

Which is exactly what happened in the early 80’s. The global recession drastically reduced the price consumers could pay for refinery products. As a result the refineries reduced the price they paid for crude oil. And all this happened as OPEC greatly decreased its production rate.

IOW OPEC reducing production DID NOT lead to higher oil prices. In fact as it cut production prices continued to drop. So we can toss the “OPEC cutting production will increase oil prices” bumper sticker away. It wasn’t that simple in the 80’s and it’s not that simple today.

Refineries would not be paying $62+/bbl to if they projected that consumers wouldn’t buy products at a high enough price to generate a refinery profit. And if refineries see an increasing ability for consumers to pay more competition will drive them to pay more for oil. But if tomorrow they refineries projected a drastic decline in consumer affordability the price of oil will also decline drastically. And that will happen even if OPEC et al cut production significantly. Just as it did in the 80’s. There is no single factor that determines the price of oil.

Which leaves the simple minded very confused. LOL.

Boat on Wed, 24th Jan 2018 11:35 am

Rock,

“oil producers do not set the price they sell their oil for. But they can adjust the volume the produce which might have some effect”

No shyt. It has a lot of effect. A pipeline explosion has an immediate effect. A huge storm, immediate effect. Even the perception of conflict can have an immediate effect without a barrel lost, It’s not that complex as you make it to be. Supply and demand rule and the market adjusts on rumor or real volume events. OPEC/Russia did cut production and as oil storage levels fell the price has increased. Markets set the price, not refineries. Markets balance supply and demand over time.

Davy on Wed, 24th Jan 2018 11:46 am

“Supply and demand rule”

Today it is different with economic repression of the cost of money and and liquidity management with easing or tapering. Lets see what happens in another shock. This surely will happen because business cycles do happen in a cyclic world. IOW, supply and demand rule within a new financially managed world.

Boat on Wed, 24th Jan 2018 12:02 pm

Davy,

We can probably agree another shock will come and the higher price of oil may even kick start the downward trend. The good news is 2/3 of the worlds energy/electricity is still cheap which establishes a baseline of stability. Growth but slower growth is our medium term future.

cheap

Davy on Wed, 24th Jan 2018 12:10 pm

I hope so, boat but I am not willing to bet on it. It just feels like it because of the habituation of years of the same. I feel this time is different but hopefully I am wrong.

Boat on Wed, 24th Jan 2018 12:12 pm

If it were not for Venz I would be much more bullish. The US, Canada and a couple other smaller players can keep up with demand but venz may upset the supply side. So far so good with Nigeria, Lybia and Iran but they also pose risk. Time will tell. Maybe China bails out venz as they have the most to lose with higher oil prices.